Photo from Pexels by slon_dot_pics

It’s said that everything on a computer is either a file or process. In a strictly binary way, all computer data is just a combination of 1s and 0s; therefore, files are simply data that’s stored, typically on the hard disk or in memory (RAM), while processes are the manipulation of that data – usually in the CPU. Here, we’ll be reviewing different ways to view those files on a Linux system.

OVERVIEW

Today, we’ll be covering basic Linux filesystem navigation: abstraction, location, viewing, and finding. This will enable us to understand how files are organized & structured, how to list & parse files, and how to find what we’re looking for.

Outline

- File System Structure

- Manila Folders

- System Directories

- File Paths

- The Root Directory

- Absolute Paths

- Relative Paths

- “Dot” Paths

- Tab Completion

- Viewing

- Files & Folders

- Long Listing

- Hidden Files

- Home Directory

- Finding

- Which

- Find

- Locate

Prerequisites

- Basic Linux CLI Operations

FILE SYSTEM STRUCTURE

Manila Folders

First, the file system’s structure needs to be understood conceptually. Luckily, file systems are a lot like manila folders that hold more folders or sheets of paper.

So, imagine a folder labeled “Income Taxes”. In it, you have 3 more folders labeled by year: “2001”, “2002”, and “2003”. In each of those folders, you have a mix of paperwork and folders for each employer you’ve had: “job1” and “job2”. The “job” folders hold most of your paperwork: W2s, paycheck stubs, and such. Altogether, the folder hierarchy might look like this (folders are bolded and underlined):

- Income Taxes (folder)

- 2001 (folder)

- 1040-EZ Form (paperwork)

- Job 1 (folder)

- Paycheck 1 (paperwork)

- W2 (paperwork)

- 2002 (folder)

- 1099-MISC Form (paperwork)

- Job 1 (folder)

- Paycheck 2 (paperwork)

- W2 (paperwork)

- Job 2 (folder)

- Paycheck 3 (paperwork)

- W2 (paperwork)

- W4 Form (paperwork)

- 2003 (folder)

- Job 2 (folder)

- Paycheck 4 (paperwork)

- W2 (paperwork)

- Job 2 (folder)

- 2001 (folder)

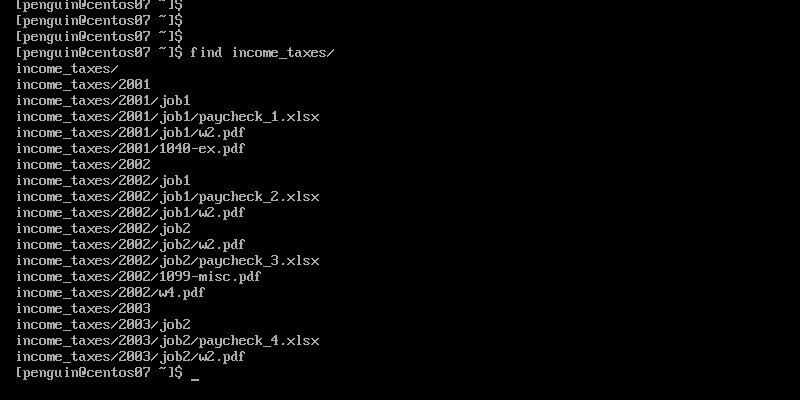

System Directories

Now, imagine (1) each folder as a Linux directory and (2) each sheet of paper as a Linux file. The file system equivalent might look like this (directories are bolded, underlined, and have a trailing slash):

- income_taxes/

- 2001/

- 1040-ex.pdf

- job1/

- paycheck_1.xlsx

- w2.pdf

- 2002/

- 1099-misc.pdf

- job1/

- paycheck_2.xlsx

- w2.pdf

- job2/

- paycheck_3.xlsx

- w2.pdf

- w4.pdf

- 2003/

- job2/

- paycheck_4.xlsx

- w2.pdf

- job2/

- 2001/

FILE PATHS

A file path – or just “path” for short – is the location of a file/directory from another directory in the file system hierarchy.

The Root Directory

The beginning of the file system hierarchy is the top-level directory, often referred to as the “root directory” or “slash”.

NOTE: The root directory vs the root user’s directory

Be careful not to confuse the root directory with the “root” user’s home directory.

– The root directory: /

– The root user’s home directory: /root/

Absolute Paths

An absolute path always starts from the root directory to a file/folder’s location in the hierarchy. Using the above example, if the “income_taxes” directory is in root directory, here are what all the absolute paths would look like for each file and directory (directories are bolded and highlighted):

- /income_taxes/

- /income_taxes/2001/

- /income_taxes/2001/1040-ex.pdf

- /income_taxes/2001/job1/

- /income_taxes/2001/job1/paycheck_1.xlsx

- /income_taxes/2001/job1/w2.pdf

- /income_taxes/2002/

- /income_taxes/2002/1099-misc.pdf

- /income_taxes/2002/job1/

- /income_taxes/2002/job1/paycheck_2.xlsx

- /income_taxes/2002/job1/w2.pdf

- /income_taxes/2002/job2/

- /income_taxes/2002/job2/paycheck_3.xlsx

- /income_taxes/2002/job2/w2.pdf

- /income_taxes/2002/w4.pdf

- /income_taxes/2003/

- /income_taxes/2003/job2/

- /income_taxes/2003/job2/paycheck_4.xlsx

- /income_taxes/2003/job2/w2.pdf

Relative Paths

Conversely, a relative path starts from a specific directory to a file/folder’s location in the hierarchy. Continuing with the same “income_taxes” model as before, here are a few examples of different relative paths:

- From the “income_taxes” directory:

./2001/1040-ex.pdf - From the “2002” directory:

./1099-misc.pdf

Although rare, a relative path can also be defined from the / directory, which would make it look similar to an absolute path:

- From the “/” directory:

./income_taxes/2003/job2/paycheck_4.xlsx

“Dot” Paths

When a dot (.) is used where a path is expected, it represents the CWD (Current Working Directory). For example, if you execute ls, ls ., or ls ./, they should all display the same output.

Now, if you use a double-dot (..) it means “up” one directory in the hierarchy. So, if you are in the “2002” folder and execute ls .. or ls ../, you’ll see the contents of the “income_taxes” directory.

You can use as many dots as you’d like to go up the directory tree; for example:

[penguin@centos07 job2]$ pwd

/income_taxes/2003/job2

[penguin@centos07 openssl]$ cd ../../..

[penguin@centos07 /]$ pwd

/Tab Completion

In addition to commands, tab completion works for file paths as well and can be used to navigate through a file system quickly. To use tab completion, begin typing a path and hit “Tab” (perhaps twice). All the possible path options will be displayed for you (much like executing the `ls` command):

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ /

bin/ dev/ home/ lib64/ mnt/ proc/ run/ srv/ tmp/ var/

boot/ etc/ lib/ media/ opt/ root/ sbin/ sys/ usr/

Now, to narrow the possibilities down, begin typing part of the path. For example, typing `/b` and hitting “Tab” will display all the paths that start with `/b`:

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ /b

bin/ boot/

Next, type /bi and hit “Tab”. Since there is now only one possible file/directory that starts with “/bi”, the rest of the path will be filled in for you:

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ /bin/

From here, you can repeat the process: press “Tab” to see the available options under /bin/. However, since there are many possible paths to display, you’ll be prompted to continue:

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ /bin/

Display all 734 possibilities? (y or n)

NOTE: y for “yes”

If you hit y here, you’ll see a long list of files. From here, press Enter to scroll down until you reach the bottom of the list or hit q to exit.

Enter n for now and narrow the list down by typing /bin/whoa and hit “Tab”. Again, since there is only one possibility, the remainder will be automatically filled in for you:

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ /bin/whoami

Tab completion for paths is often used in conjunction with commands as well. For example, typing cat /home/penguin/ and hitting “Tab” could result in the following:

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ cat /home/penguin/

.bash_history .bash_logout .bash_profile .bashrc Directory/ Folder/ .lesshst

From here, continue to type part of the directory or file you want to specify and hit “Tab” as needed until you reach the desired full path:

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ cat /home/penguin/

.bash_history .bash_logout .bash_profile .bashrc Directory/ Folder/ .lesshst

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ cat /home/penguin/Directory/

AnotherDirectory/ duplicate.png MyNewFolder/ picture.png

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ cat /home/penguin/Directory/AnotherDirectory/

bar.txt foo.txt

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ cat /home/penguin/Directory/AnotherDirectory/foo.txt

Finally, you can hit “Enter” to actually execute the full cat command:

[penguin@centos7 ~]$ cat /home/penguin/Directory/AnotherDirectory/foo.txt

Hello World!

On the other hand, observe the following example in which there is only one file/folder in each directory:

[brian@centos7 TestFolder]$ pwd

/home/brian/TestFolder

[brian@centos7 TestFolder]$ ls

OneDirectory

[brian@centos7 TestFolder]$ ls OneDirectory/

OneFolder

[brian@centos7 TestFolder]$ ls OneDirectory/OneFolder/

OnlyDir

[brian@centos7 TestFolder]$ ls OneDirectory/OneFolder/OnlyDir/

only_file.txt

When tab completing, since there is only one possible file/folder per directory, they will be filled in automatically – no need to enter a partial path at all. Simply typing cat (notice the space after cat here) and hitting “Tab” four times will result in the following path:

[brian@centos7 ~]$ cat OneDirectory/OneFolder/OnlyDir/only_file.txt

NOTE: Avoid Typos

Another benefit from tab completion is confirmation that the path you’re using is without any typos.

VIEWING

Files & Folders

When browsing a file system, since folders appear to contain files within them, it might seem that folders themselves are not files. However, recall that all data on a computer is either a file or process – This means that folders, a.k.a. directories, are just a special type of file.

NOTE: Special Files

Some other special types of files:

– links

– sockets

– devices

Long Listing

To view files, and some info about them, use the long listing command: ls -l.

[penguin@centos07 somedir]$ ls -l

total 0

drwxrwxr-x. 2 root bear 6 Jul 18 16:20 bar

-rw-r--r--. 1 penguin root 0 Jul 18 16:20 foo.cfg

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 penguin penguin 9 Jul 18 16:21 spam -> /tmp/eggsThe 1st field of each line: the first letter/symbol tells you what kind of file it is (the remaining letters and dashes describe the permissions)

NOTE: Common File Types

Here are the most common file types you’re likely to see:

– - = normal file

– d = directory

– l = link

The 2nd field: the number of links to the file

The 3rd field: represents the user associated with the file

The 4th field: represents the group associated with the file

The 5th field: the size of the file (default is in bytes)

The 6th – 8th fields: when the file was last modified

The 9th field: the file/directory name

Hidden Files

Often, there are “hidden” files on the system – these are files/folders that are preceded with a . in the name. When files are hidden, they can only be seen when explicitly searched for.

NOTE: Why Hide Files?

Hidden files have multiple purposes, but it’s mainly to (1) deter accidental deletion/modification of important files and (2) obscure static files from cluttering up the screen when browsing.

To view these files, use the -a flag to view “all” files: ls -al

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ ls -al

total 20

drwx------. 3 penguin penguin 111 Jul 18 16:24 .

drwxr-xr-x. 7 root root 70 Jul 18 16:10 ..

-rw-------. 1 penguin penguin 1497 Jul 18 16:21 .bash_history

-rw-r--r--. 1 penguin penguin 18 Aug 8 2019 .bash_logout

-rw-r--r--. 1 penguin penguin 193 Aug 8 2019 .bash_profile

-rw-r--r--. 1 penguin penguin 231 Aug 8 2019 .bashrc

drwx------. 2 penguin penguin 29 Jul 16 17:08 .ssh

-rw-------. 1 penguin penguin 670 Jul 18 16:06 .viminfoHere’s an example of how hidden files can prevent accidental deletion:

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ pwd

/home/penguin

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ ls -a

. .. bar .bash_history .bash_logout .bash_profile .bashrc foo.txt .ssh .viminfo

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ rm -rf ./*

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ ls -a

. .. .bash_history .bash_logout .bash_profile .bashrc .ssh .viminfoOnly the bar directory and foo.txt file were deleted while the hidden files remain.

Home Directory

Each Linux system has a directory, called “home”, located here: `/home/`. By default, most users have a home directory within `/home/` that is named after the user:

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ ls -ald /home/*

drwx------. 2 anna anna 62 Jul 18 15:57 /home/anna

drwx------. 2 bear bear 62 Jul 18 16:10 /home/bear

drwx------. 2 brian brian 62 Jul 18 15:58 /home/brian

drwx------. 3 penguin penguin 111 Jul 18 16:24 /home/penguin

drwx------. 2 zeta zeta 62 Jul 18 15:58 /home/zeta

Since the home directory is often referenced, it has a shortcut: `~`. So, `~` is equivalent to `/home/<UserName>/`. For example, if you are logged in as the user `anna` and execute the `ls ~` command, you’ll see the contents of your home directory: `/home/anna/`.

[anna@centos7 ~]$ pwd

/home/anna

[anna@centos7 ~]$ ls

bar.txt foo.txt

[anna@centos7 ~]$ ls ~

bar.txt foo.txt

[anna@centos7 ~]$ ls ~/

bar.txt foo.txt

The `~` also works for changing directories:

[anna@centos7 ~]$ cd /tmp

[anna@centos7 tmp]$ pwd

/tmp

[anna@centos7 tmp]$ cd ~

[anna@centos7 ~]$ pwd

/home/anna

FINDING

Which

If you want to find where a command is located in the files system, use the which command, followed by the command you want to search for: which <SomeCommand>. For example, if you want to find where the hostname command is:

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ which hostname

/bin/hostnameFind

To list all files and directories – including hidden files – from your present working directory, you can use the find command. By default, this action is recursive, meaning that the find command will list everything from all subdirectories as well:

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ find

.

./.bash_logout

./.bash_profile

./.bashrc

./.bash_history

./.ssh

./.ssh/authorized_keys

./.viminfoNow, to specify a different directory, simply type find followed by the directory you want: find /<PathToDirectory>/.

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ find /etc/

/etc/

/etc/fstab

/etc/crypttab

/etc/mtab

/etc/resolv.conf

/etc/grub.d

find: ‘/etc/grub.d’: Permission denied

/etc/terminfo

...If you want to list the files only, use the -type f option:

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ find /etc/ -type f

/etc/fstab

/etc/crypttab

/etc/resolv.conf

find: ‘/etc/grub.d’: Permission denied

/etc/magic

...Similarly, if you just want to list directories, use the -type d option:

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ find /etc/ -type d

/etc/

/etc/grub.d

find: ‘/etc/grub.d’: Permission denied

/etc/terminfo

...NOTE: Options for find

There are many useful options for the find command: finding files by modification time (older or newer), user, and permissions; also, executing commands against the found files/directories. Use the manual page to see more details: man find.

Locate

To search for a specific file/directory that you already know the name of, you can use the locate command (from the mlocate package) followed by the name, or part of the name:

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ locate fstab

/etc/fstab

/usr/lib/dracut/modules.d/95fstab-sys

/usr/lib/dracut/modules.d/95fstab-sys/module-setup.sh

/usr/lib/dracut/modules.d/95fstab-sys/mount-sys.sh

/usr/lib/systemd/system-generators/systemd-fstab-generator

/usr/share/man/man5/fstab.5.gz

/usr/share/man/man8/systemd-fstab-generator.8.gz

/usr/share/vim/vim74/syntax/fstab.vimHowever, if a known file/directory cannot be found, it’s likely that updatedb needs to be run (with sudo privileges).

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ sudo updatedbupdatedb registers all the current files on the system so the locate command can find them. So, if you’ve just created a new file, updatedb would need to be run before locate could find that file:

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ ls -l

total 0

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ touch findme.txt

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ ls -l

total 0

-rw-rw-r--. 1 penguin penguin 0 Jul 19 19:40 findme.txt

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ locate findme

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ sudo updatedb

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ locate findme

/home/penguin/findme.txtIn contrast, if a file has just been deleted, locate will “think” that file still exists until updatedb is run again:

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ ls -l

total 0

-rw-rw-r--. 1 penguin penguin 0 Jul 19 19:40 findme.txt

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ rm -f findme.txt

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ ls -l

total 0

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ locate findme

/home/penguin/findme.txt

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ sudo updatedb

[penguin@centos07 ~]$ locate findmeCONCLUSION

These are the basics of file system navigation. Now, we can move around, understand where files are, and how to find them.

- System directories are like manila folders

- Absolute and relative file paths

- Listing hidden files

- Finding files and directories

To learn more about file systems, see Linux top-level directories.